Advisor Blog | Aug 2021

COVID-19 Retrospective: Adjustments to Incentive Plan Outcomes and the Shareholder Response

Did the companies making executive compensation adjustments due to COVID experience any shareholder or advisory firm push-back?

The COVID-19 pandemic was something of a perfect storm in 2020’s annual compensation planning cycle. When reports of the virus’s spread were far from US shores, boards and compensation committees were approving annual operating plans and incentive plan goals as per usual.

Only a few weeks later, as the world was upended, these freshly-approved goals were either disconnected from reality or no longer in line with more pressing strategic priorities.

I’ve recently spoken about how COVID-19 wasn’t the first global disruption we’ve seen significantly impact executive compensation plans (e.g., 9/11 and the 2008 financial crisis), and it surely won’t be the last. However, the pandemic was the first such disruption to occur in the say-on-pay era, which allows us to learn not only how companies responded to the crisis, but whether they faced any significant shareholder and/or advisory firm resistance to the actions they took.

Preliminary feedback from shareholders and advisory firms

Early in the crisis, while committees were deliberating whether to reset incentive plan goals or simply “ride it out” (and potentially apply discretion at the end of the year), the major shareholder advisory firms signaled cautious, conditional support of well-reasoned adjustments.

ISS acknowledged that boards were likely to “materially change the performance metrics, goals, or targets used in their short-term compensation plans in response to the drop in the markets,” but encouraged contemporaneous disclosure to shareholders to explain the rationale for such changes.

Likewise, Glass Lewis also signaled their desire for thoughtful disclosure of any changes, particularly for companies with the most strained circumstances: “…If the company has exercised upward discretion on performance or payouts more directly, we expect a thorough and compelling justification… All companies, especially those seeking support from governments or executing significant employment cuts, should consider the reputational risk associated with poor pay decisions.”

Shareholders, for their part, also reiterated the general desire for rigorous disclosure related to any mid-cycle adjustments or discretion. A few institutional investors took a more hardline stance against mid-cycle adjustments, reasoning that shareholders were unable to insulate themselves from the pandemic’s impact, and executive teams shouldn’t be able to either. These critiques applied even more so to companies that experienced mass layoffs or accepted government assistance.

Incentive plan actions taken by Fortune 100 companies

Now that we’ve fully emerged from the 2021 proxy season (and partially emerged from the pandemic), we are able to learn from proxy disclosures how companies reacted to COVID’s impact on their incentive plans. The data below reflects a study of the proxy filings published by Fortune 100 companies (as of July 24, 2020 to May 31, 2021[1]). For nearly all of these companies, this reflects their proxy disclosure for the fiscal year most directly impacted by the pandemic.

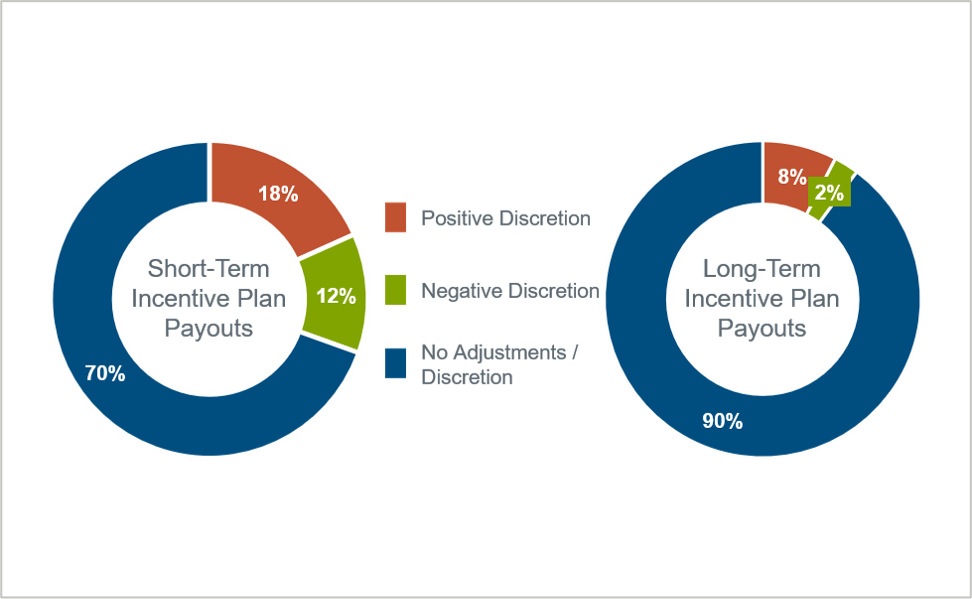

Our study found that the majority of companies elected not to exercise discretion to either their short- or long-term incentive plan payouts, but for those that did, discretion was: (i) more common in annual plans, and (ii) more often used to increase payouts vs. unadjusted outcomes.

For the purposes of this study, “discretion” was broadly defined to include any adjustment or action taken by a compensation committee that resulted in higher or lower payouts for executive officers than would have otherwise been achieved if no action was taken. In many cases, this reflected application of traditional discretion to adjust payouts from formulaic outcomes at the end of a performance period, while in other cases, it reflected differences in formulaic payout outcomes that resulted from mid-year adjustments to incentive plan goals or payout formulas (e.g., lowering financial goals).

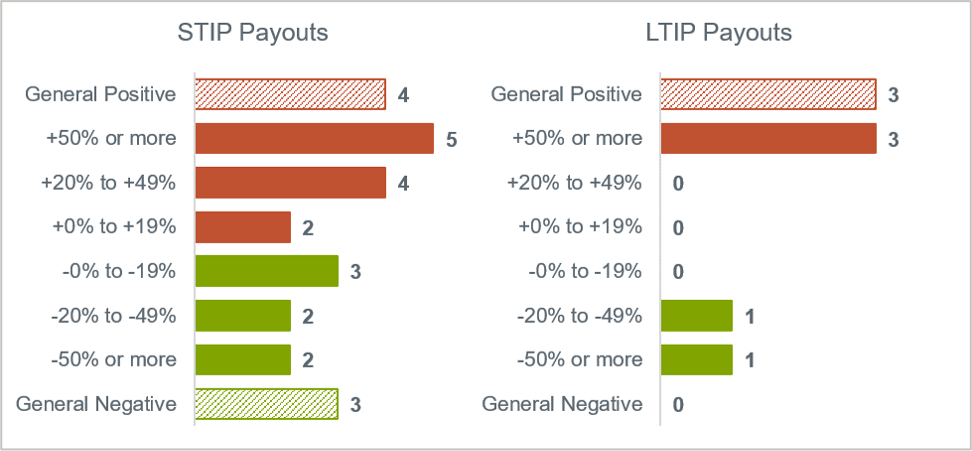

In terms of the degree of COVID-related discretion/adjustments on impacted payouts[2], we found that adjustments in long-term incentive (LTI) plans were generally more extreme (i.e., +/- 50% or more) versus short-term incentive (STI) plans, where we observed more willingness to make finer payout adjustments.

The prevalence of discretion being higher in annual plans (30%) versus long-term plans (10%) was anticipated. By their nature, short-term incentive plans are more susceptible to outside shocks. Short-term goals are more precise, with narrower performance ranges than their long-term counterparts, which are ideally built to accommodate the uncertainty that comes with a longer performance period. Also, short-term incentive plans are far less likely to have relative goals that can stand up to unexpected headwinds.

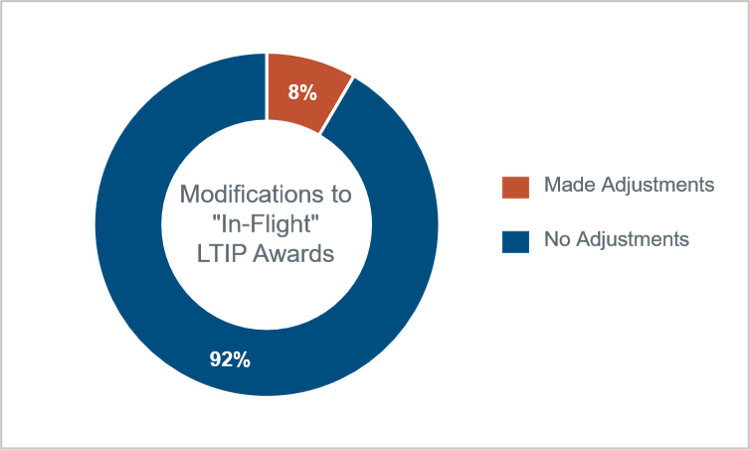

It’s therefore unsurprising that we also found very few companies disclosed changes to in-progress long-term performance plans due to the impact of the pandemic.

Shareholder and advisory firm response to incentive plan adjustments

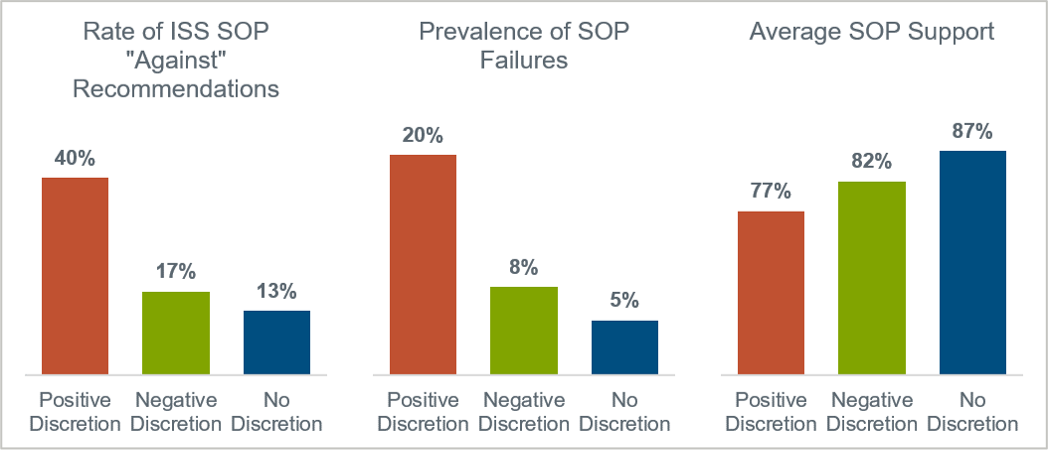

It was expected that companies exercising discretion to increase payouts for executives would receive additional scrutiny from shareholders and advisory firms, and that proved to be the case.

For companies that exercised positive discretion to incentive plan payouts in the midst of the pandemic: (i) rates of ISS opposition were notably higher vs. companies that made no adjustments, (ii) say-on-pay vote results were lower, and (iii) say-on-pay failures were far more common.

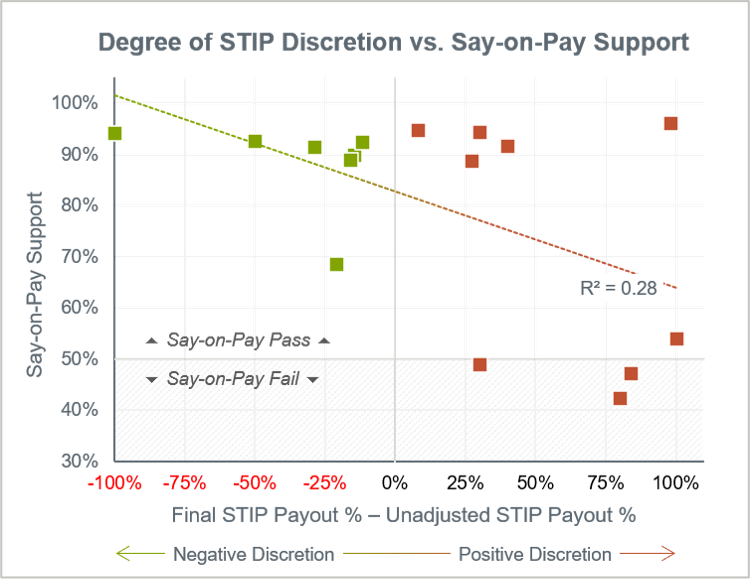

Furthermore, when we plotted the degree of discretion applied by a company to their executive’s short-term incentive plan payouts[3] against the level of say-on-pay support they received, a pattern emerged. That is, as the degree of positive discretion applied to payouts increased, so did the prevalence of low or even failed say-on-pay votes.

Summary

In an earlier blog, I spoke about the exposure risk for companies that make incentive plan adjustments without a clear-cut rationale. Committees were told to expect more scrutiny for these types of adjustments, and as it turned out, that scrutiny had some real teeth.

Fear of shareholder or advisory firm pushback should never dictate compensation policy, but it should certainly inform it. Committees must always do what they feel is in the best interest of the company (and not just in the best interest of executives), but in doing so, they have a duty to understand the perspectives of all stakeholders before rushing into changes.

While we certainly hope the next crisis is far away, the lessons learned from COVID-19 will provide helpful context to these future discussions for years to come.

[1] Reflects 87 publicly traded companies—the entirety of the 2020 Fortune 100 excluding private companies (10), government-sponsored enterprises (2), and master limited partnerships

[2] “Degree of Discretion” is defined as the final STI or LTI plan payout (as a percent of target) less the unadjusted STI or LTI plan payout (also as a percent of the target opportunity), where the “unadjusted” payout reflects what the payout would have been against original goals absent intervention by the committee.

[3] Scatterplot excludes companies who: (i) did not disclose sufficient information for this calculation, and/or (ii) did not have a say-on-pay vote at their most recent annual meeting of shareholders.