Article | Jan 2026

Calibrating Incentives: Effectively Structuring the Executive Compensation Payout Slope

A successfully designed performance-payout slope is central to aligning executive incentives with sustained value creation.

The eighth in a Pearl Meyer series covering Executive Compensation Essentials—a resource for every board, compensation committee, and management team—details how a well-designed performance-payout slope is critical to align executive incentives with sustained value creation.

One of the compensation committee’s primary responsibilities is establishing company performance goals that serve as the basis for executive incentive plans—for both annual and long-term performance. Since the majority of executive compensation is variable and tied to company performance, setting performance goals that are challenging and motivational, yet attainable, is foundationally important.

When establishing incentive goals, the compensation committee typically sets a range of performance expectations and associated payout outcomes. This is referred to as the performance-payout slope, which is the focus of this installment of our Executive Compensation Essentials series. The slope centers on a targeted performance objective, with an established minimum (threshold) and maximum performance objective on either side of the target. Most commonly, there are no payouts below the minimum objective and payouts are capped at the maximum objective. Ideally the performance-payout slope is structured so that in most years the company’s year-end performance outcomes will end up at some point on the slope, above minimum and below maximum.

The question is not whether to tie pay to performance, but how sharply compensation should move as performance changes. Consistently paying below minimum or at maximum can lessen the program’s motivational impacts. Thoughtful slope design helps balance motivation and risk, reinforces accountability, and ensures incentive outcomes remain meaningful across a range of business conditions.

The Starting Point: Setting Target Goals

Calibrating the performance-payout slope starts with establishing the performance target, the level at which 100% of an executive’s target incentive is paid. The target performance goal is typically based on the company’s operating plan—including its assessment of expected growth, expense management, and balance sheet discipline—and reflects what the company expects to achieve for the year.

The operating plan, which informs the target performance goal, is commonly approved by the full board of directors following a detailed review of the company’s performance expectations for the year. Often, though not always, the target performance goal ties to performance expectations communicated to shareholders, if the company provides such guidance. We normally see the target performance goal set at least at the midpoint of shareholder guidance and often toward the higher end of that guidance. The target goal should have some degree of stretch but should also be attainable if the company is able to execute on its plan for the year.

The Payout Slope: Setting Minimum and Maximums

Once the target goal is established, the compensation committee must review and approve the proposed performance-payout slope built around the target performance goal with the minimum and maximum goals defined. While market practice varies, at minimum performance the executive will typically earn between 25–50% of their target incentive and at maximum between 150–200%. Thus, the incentive: at increasingly higher levels of performance, the executive can earn increasingly higher levels of compensation. In line with market practices and good risk-mitigation governance, executive incentives are almost always capped.

There are two key and related considerations when establishing the performance-payout slope: (1) how steep the slope is, and (2) how wide the performance ranges are around the target. Following are three important considerations when making those determinations:

Impact of Metric Type: Generally, the more predictable the performance outcome is, the steeper and narrower the slope will be. A steeper, narrower slope equates to greater pay and performance sensitivity, recognizing it is more challenging to deviate from the expected results given the higher level of predictability associated with the target goal. In contrast, less predictable results often are associated with a flatter, wider slope to accommodate the likelihood of more variability in results. The potential for variability in results often ties to the performance metric used. Generally, the higher up on the income statement, the narrower the performance range around target.

Performance Metric Description Example Range Top line A narrower range of performance outcomes than other metrics. 95–105% of target Bottom line Greater likelihood of variability in results and typically a wider range around target, as profit-based metrics start with revenue but then are adjusted for expenses and non-operating items. 85–115% of target Cash flow Often a wider performance range around target than seen with profit goals, because the calculation of cash flow starts with income and then is subject to further adjustments. 80–120% of target - Goal-Setting Guidelines: When establishing the minimum and maximum performance goals, it can be helpful to consider associated expected probabilities of attaining those outcomes. A rule of thumb is that the minimum performance goal should be achieved 80–90% of the time (i.e., 8–9 years out of 10) whereas the maximum performance goal should only be achieved 10–20% of the time (i.e., 1–2 years out of 10). A helpful insight in considering probabilities is to look at your company’s historical outcomes over the past 10 years and determine the percentage of time your company was at threshold, target, and maximum performance levels.

- Market Practices: Also consider performance slope calibration among a company’s peers or industry comparables. Reviewing the slopes of peers of similar maturity, size, and industry focus can provide helpful context. For public companies, this information is often disclosed in shareholder proxy statements.

Variations in Slope Calibration

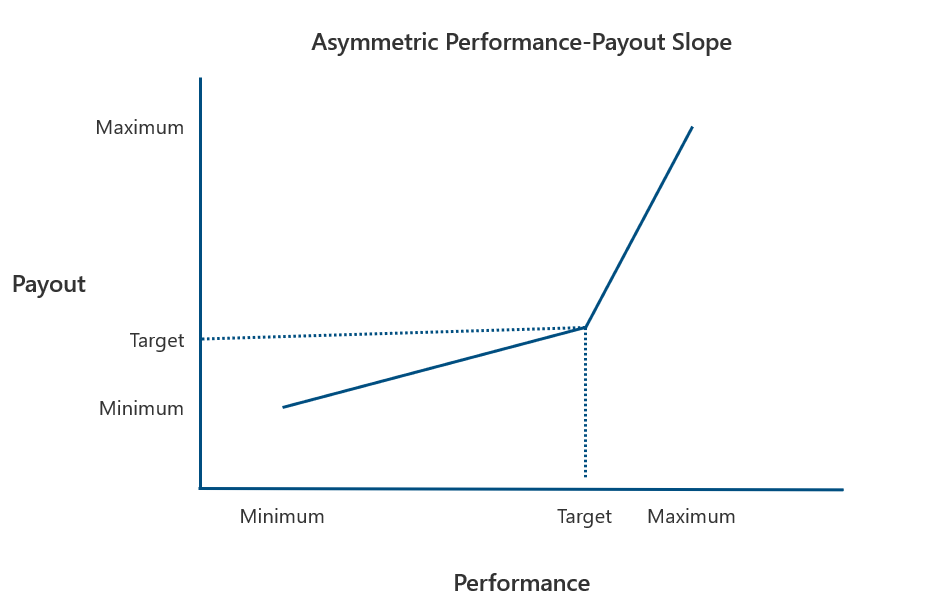

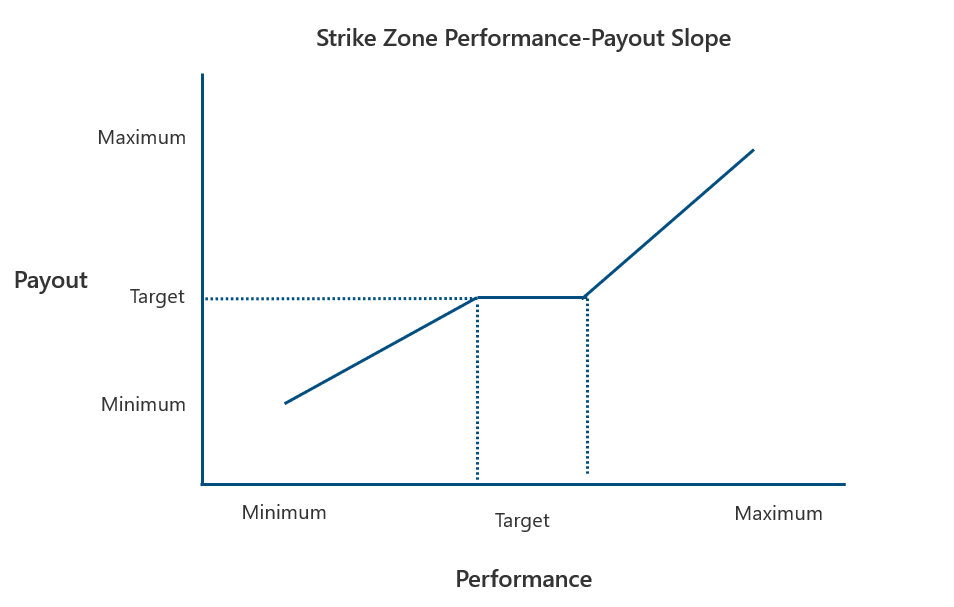

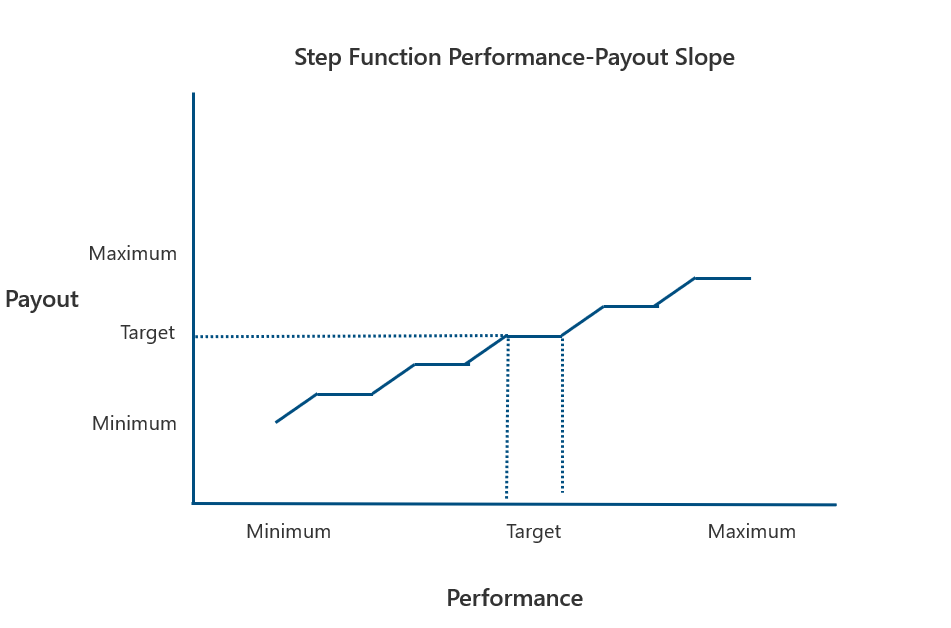

While we often see symmetric performance ranges—e.g., minimum performance objective set at 90% of the target objective and maximum performance objective set at 110%, with a straight-line interpolation of payouts for results in between those points—there are instances where the performance-payout slope may vary from that norm.

Asymmetric Slope: A performance-payout slope that is not symmetrical on each side of target may be desirable, depending on the rigor of the associated target goal. For example, if the target goal is considered a stretch goal, then it may be appropriate to consider a flatter, longer slope below target to protect the downside, and a steeper, shorter slope above target to provide higher payouts for each performance increment above target given the challenging nature of the target.

- Strike Zone: If there is a higher-than-normal expectation for variability in results around the target, it may be appropriate to consider establishing a flat slope around the target, e.g., 98−102% of target yields a 100% payout.

- Step Function: Similar to the strike zone concept, a step function slope creates mini strike zones at each point along the slope. While there is less pay-for-performance sensitivity with a step function than a linear slope, it may be appropriate in instances where there is less predictability in outcomes along the slope.

The Performance-Payout Slope Is Worth Spending Time On

An effectively designed performance-payout slope is central to aligning executive incentives with sustained value creation. By thoughtfully calibrating targets and performance ranges based on performance predictability, historical outcomes, and market practice, compensation committees can reinforce motivation, manage risk, and strengthen pay-for-performance alignment—ensuring incentive plans remain both credible and compelling over time.